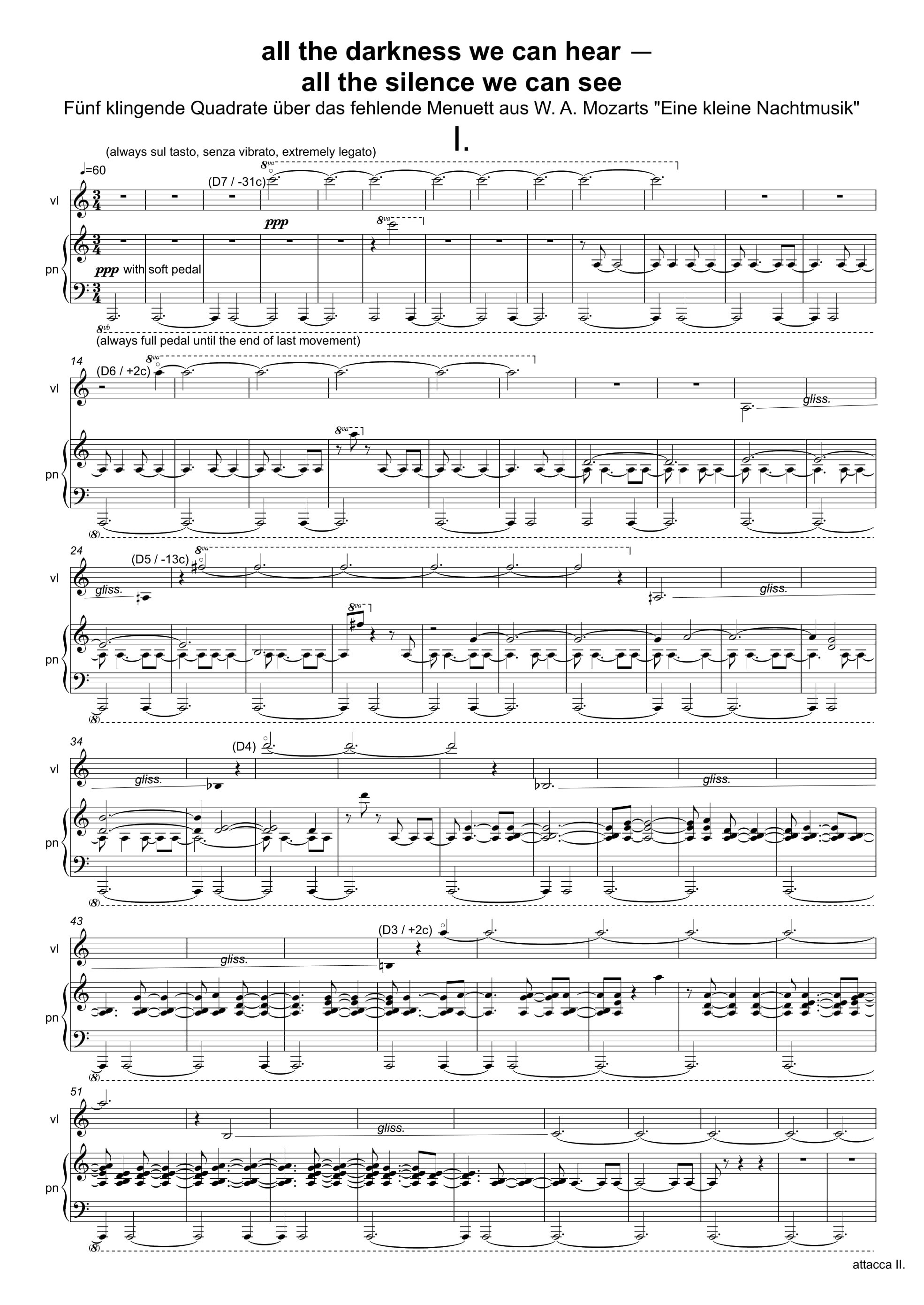

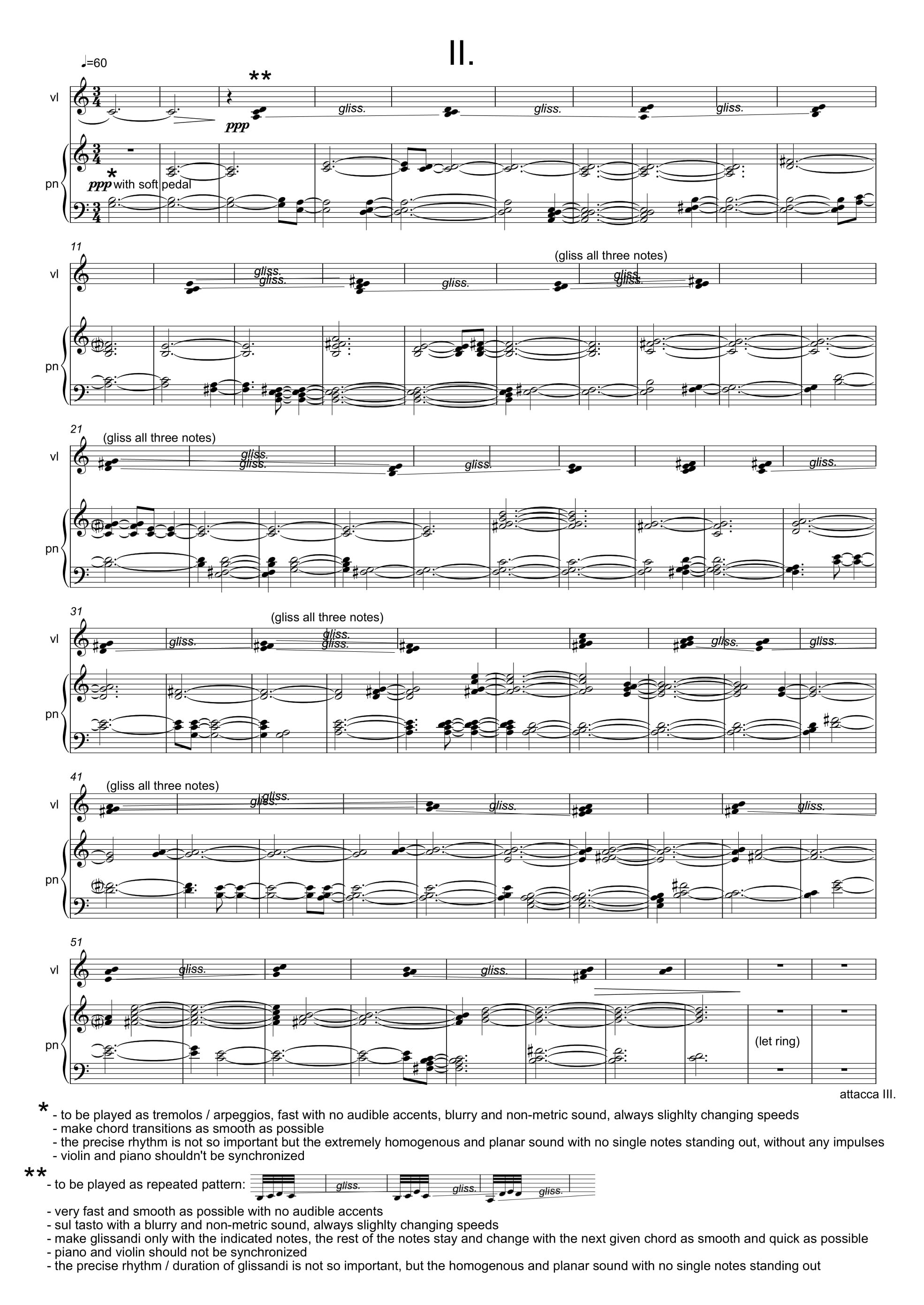

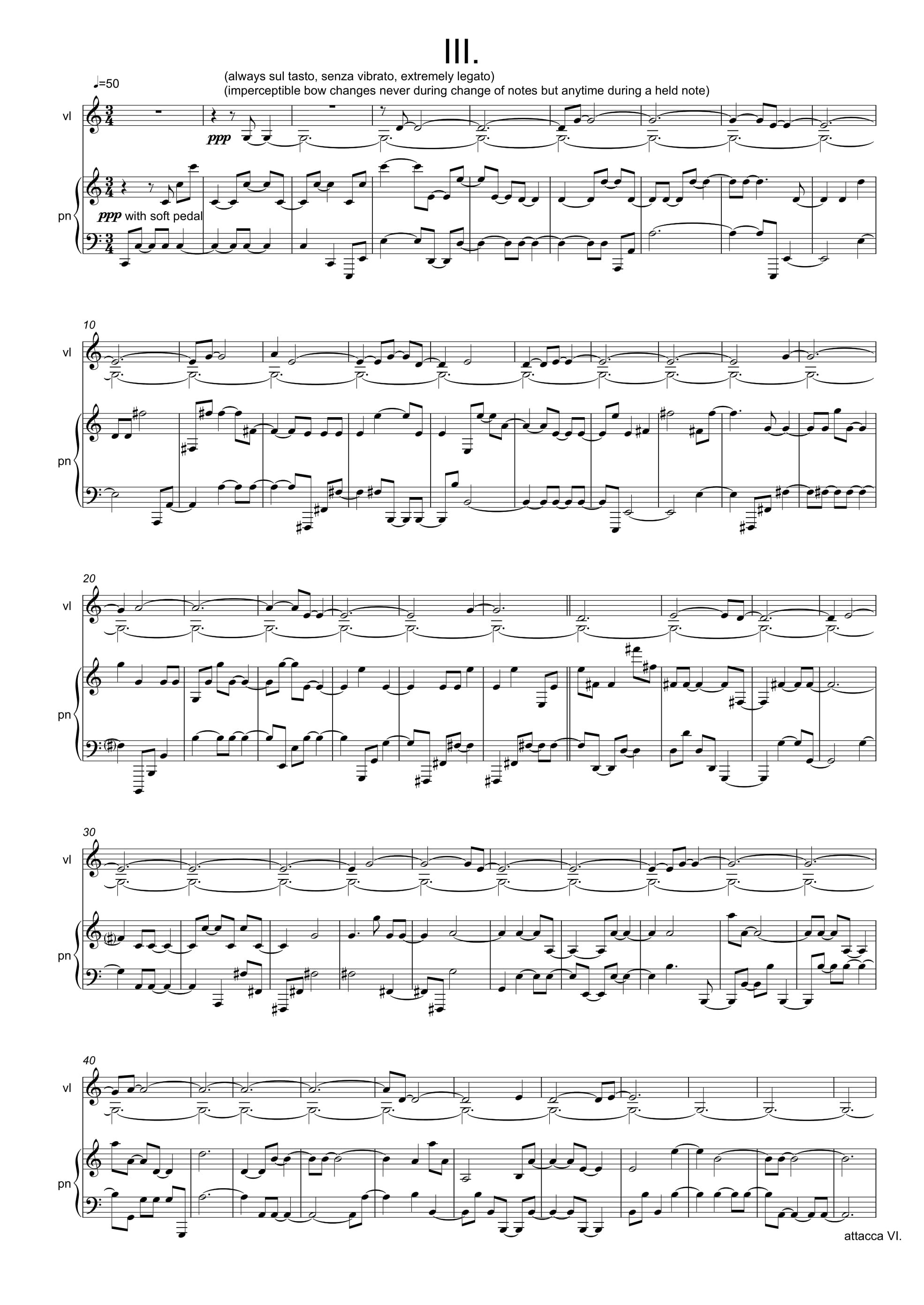

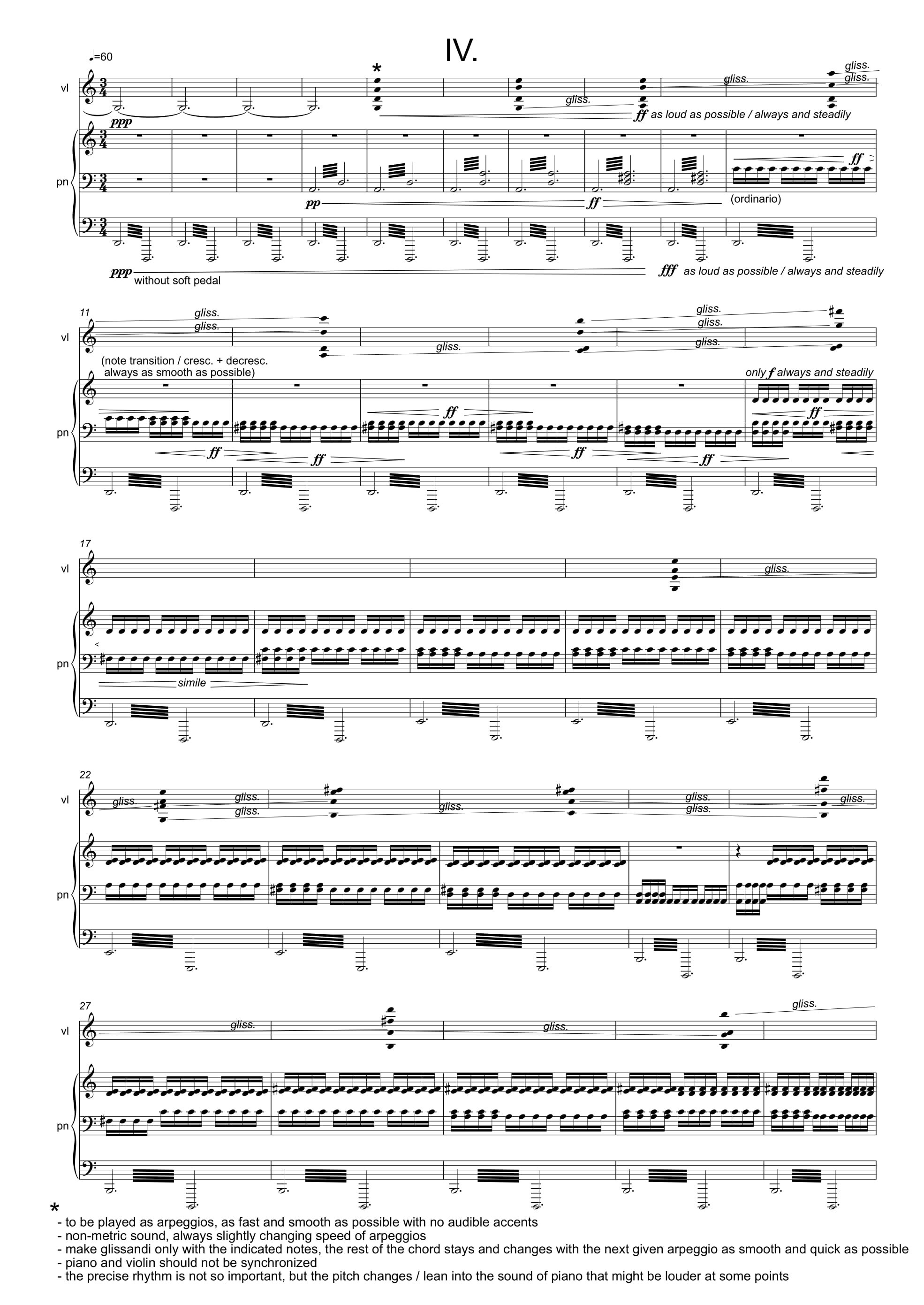

all the darkness we can hear — all the silence we can see

Fünf klingende Quadrate über das fehlende Menuett aus W. A. Mozarts “Eine kleine Nachtmusik”

[five sounding squares about the missing minuet of W. A. Mozart’s “Eine kleine Nachtmusik”]

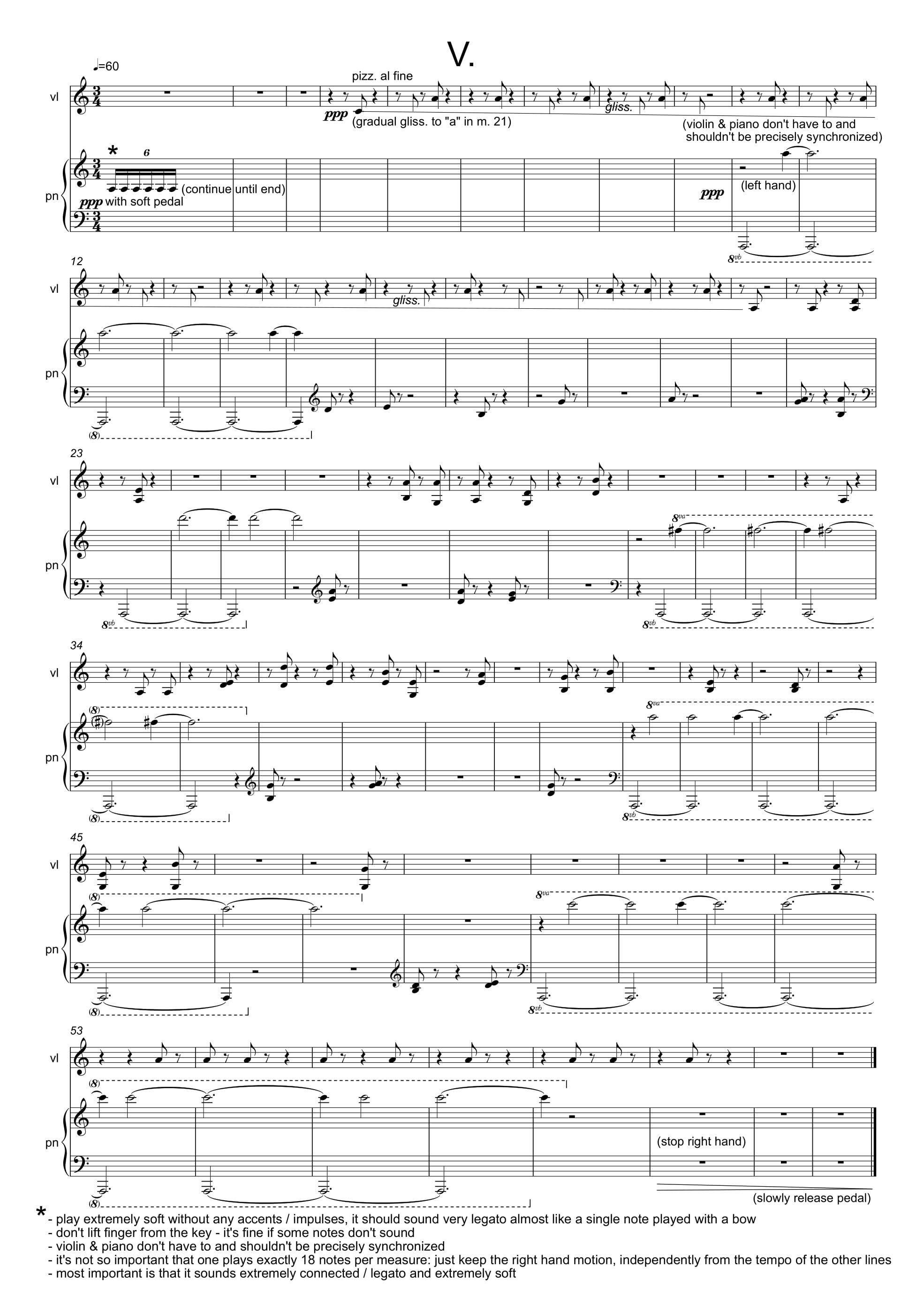

for violin and piano (2021)

duration: 15’

premiere: 17/05/2021 in the Brucknerhaus Linz, Elena Denisova (violin) and Alexei Kornienko (piano)

self-publishing edition: make contact

Es ist eigentlich ein Paradoxon, dass der Himmel erst sichtbar ist, wenn das Licht fehlt, wenn es abwesend ist. Denn normalerweise dient ja Licht dazu, Dinge sichtbar zu machen. In diesem Fall jedoch hindert uns das Licht daran, das Eigentliche, den Himmel und die unzähligen Sterne zu sehen. Es scheint, dass wir erst in der Abwesenheit des Lichts wirklich sehen können.

Auf ähnliche Weise versucht das Stück, durch Abwesenheit das Wesentliche hörbar zu machen. Dieses Wesentliche ist die Zeit, da Klang nur in der Zeit stattfinden kann. Wenn wir den Klang, die Zeit wirklich wahrnehmen, löst sich die Zeit in Zeitlosigkeit, in Abwesenheit der Zeit auf: Das bekannte Erleben eines zeitlosen Moments in einem Konzert oder auf dem Fahrrad an einem klaren Frühlingsmorgen. Die Zeit scheint also paradoxerweise stehenzubleiben, wenn wir sie wahrnehmen, wenn wir ganz in der Zeit, in der Gegenwart sind, so wie wir den leuchtenden Himmel auf einmal sehen können, wenn das Licht fehlt.

Diese Verschränkung von Hören und Sehen, von Zeit und Zeitlosigkeit findet sich u. a. auch im Titel „All the darkness we can hear – all the silence we can see“. Für mich haben die Dunkelheit und das Licht eine klingende Konsistenz, genauso wie die hörbare Stille in mir Bilder evoziert. Der Inhalt des Titels nimmt zum einen Bezug auf „Eine kleine Nachtmusik“ von W. A. Mozart und zum anderen auf die Besetzung mit Violine und Klavier. Denn in meinen Augen könnten beide Instrumente nicht weiter voneinander entfernt sein: das eine, das die Saiten streicht, das andere, das sie schlägt. Das Stück ist ein Versuch, diese beiden Extreme zu beleuchten, zu durchdringen, einander anzunähern und zu verschränken.

Der Bezug zu W. A. Mozarts „Eine kleine Nachtmusik“ wird – unter anderem – auch auf formaler Ebene deutlich. So umfasst das Stück, wie die ursprüngliche Streicherserenade auch, insgesamt fünf Sätze. Was mich fasziniert, ist die Tatsache, dass wir lediglich vier Sätze der fünfsätzigen „Kleinen Nachtmusik“ kennen, da ein Menuett-Satz verschollen ist. Fast scheint es so, als sei das fehlende Menuett, die unbekannte Abwesenheit, das Epizentrum der bekannten „Nachtmusik“: Vielleicht ist die Serenade gerade durch eben dieses Fehlen, durch diese Abwesenheit ein zeitloses Stück geworden? Natürlich ist das eine Überspitzung, zumal vielen nur der erste Satz geläufig ist. Dennoch sehe ich das fehlende Menuett als essentiellen Bestandteil der klar strukturierten Streicherserenade an, weshalb ich mich entschieden habe, gleichsam fünf leere Quadrate als hörbar gemachte Zeit zu durchleuchten.

Erst im Dunkeln scheint alles möglich, wird das Unsichtbare sichtbar. Wir sind an den Dingen interessiert, die wir nicht erklären können. Denn die Dinge, die wir vollständig erklären können, bedürfen keiner weiteren Investigation. Doch hierbei tut sich ein letztes Paradoxon auf: Je präziser, achtsamer und genauer man hinschaut, desto mehr Fragen ergeben sich, viel mehr, als beantwortet werden, selbst bei alltäglichen Dingen. Man sollte sich also hüten, allgemein Bekanntes vermeintlich für erklärbar zu halten, nur weil man sich die richtigen Fragen nicht gestellt hat. Erst eine achtsame Präzisionsanstrengung führt zu einer ungeahnten Fülle der Freiheit. Vielleicht schmeckt ja jeder Apfel doch anders und einzigartig?

(Jan David Schmitz gewidmet)

ENGLISH TEXT

It is actually a paradox that the sky is only visible when light is missing, when it is absent. Normally, light is used to make things visible. In this case, however, the light prevents us from seeing the real thing, the sky and the countless stars. It seems that only in the absence of light can we really see.

In a similar way, the piece tries to make the essential audible through absence. This essence is time, as sound can only take place in time. When we truly perceive sound, when we perceive time, time dissolves into timelessness, into absence of time: We all had the familiar experience of a timeless moment in a concert or on a bicycle on a clear spring morning. Time thus paradoxically seems to stop when we perceive it, when we are fully in time, in the present, just as we can see the luminous sky all at once when the light is absent.

This interweaving of hearing and seeing, of time and timelessness is also found, among other things, in the title "all the darkness we can hear - all the silence we can see". For me, the darkness and the light have a sounding consistency, just as the audible silence evokes images in me. The title refers on the one hand to the "Kleine Nachtmusik" by W. A. Mozart and on the other hand to the instrumentation with violin and piano. For in my eyes, the two instruments could not be further apart: the one that strokes the strings, the other that strikes them. The piece is an attempt to illuminate these two extremes, to interpenetrate them in an appreciative way, to intertwine them.

The reference to W. A. Mozart's "Eine kleine Nachtmusik" is also clear on a formal level. For example, the piece comprises a total of 5 different movements, just like the original string serenade. What fascinates me is the fact that we only know 4 movements of the five-movement "Eine kleine Nachtmusik", since a minuet movement has been lost. It almost seems that the missing minuet, the unknown absence, is the epicentre of the well-known "Nachtmusik": perhaps it is precisely this disappearance, this absence, that has made the Serenade a timeless piece? Of course, this is an exaggeration, especially since many people are only familiar with the first movement. Nevertheless, I see the missing minuet as an essential component of the well-known serenade, which is why I have decided to illuminate 5 empty squares, as it were, as time made audible.

For only in the dark does everything seem possible, does the invisible become visible. We are interested in the things we cannot explain. For the things that we can fully clarify do not need further investigation. But here a final paradox opens up: the more precise, attentive and exact one looks, the more unanswered questions open up rather than being answered. So we should be careful not to think that things that are generally known are only supposedly explainable. Only the mindful effort of precision leads to an unimagined fullness of freedom. Maybe every apple tastes different after all?

(Dedicated to Jan David Schmitz)